Palei Hamu Craok, more commonly known by its Vietnamese name Bàu Trúc, is a quaint village nestled within the town of Phước Dân, located in the Ninh Phước District of Ninh Thuận province, Central Vietnam. It has gained international recognition for its exceptional pottery craftsmanship. The sale of these time-honored ceramics, which encompasses a diverse range of products from agricultural tools to kitchenware and even children’s toys, attracts hordes of tourists to the village annually. Despite its fame, there remains a limited understanding of the traditional production methods, the local perspective on various production genres, and the deeply rooted belief systems that have been an integral part of this centuries-old process.

Exploring Bàu Trúc: A Journey Through History and Culture

Bàu Trúc, located just a short motorcycle ride away from Phan Rang-Thap Cham city in Central Vietnam, is situated approximately 9 kilometers to the south, off National Highway 1A. It might easily escape your notice were it not for the occasional tourist bus that passes through. Presently, the village is spread across two quarters within Phước Dân town: the 7th and the 12th Quarter. According to statistical data from 2018, the 7th Quarter is home to nearly 3000 residents, making it akin to a small town in its own right, with an overwhelmingly Cham ethnic population of 94%. In contrast, the 12th Quarter houses around 2000 people, with only 45% identifying as Cham, while the remaining residents are of Vietnamese ethnicity.

The name Palei Hamu Craok has its roots in the Austronesian Cham language of Southeast Asia. ‘Palei’ serves as a descriptor for villages and small towns, ‘hamu’ refers to rice paddy land, and ‘craok’ denotes a land protrusion found just upstream of the confluence of two streams. This village’s history dates back to possibly before the 9th century and even before the 12th century. During the reign of Minh Mang (1820-1840 CE), the Vietnamese annexed the region and renamed it ‘Vĩnh Thuận,’ a name still used by Vietnamese residents in the area. However, in 1964, a massive flood in the province necessitated the relocation of the village center to a nearby area, adjacent to a lake known as Danaw Panrang. ‘Panrang’ was the original Cham name for the largest city in the area, while ‘Danaw’ in Cham means ‘lake.’ Due to another meaning of ‘panrang’ as ‘area of many bamboo trees,’ the local Vietnamese began calling the new settlement ‘Bàu Trúc,’ or ‘Bamboo Lake.’

Exploring Bàu Trúc: A Journey Through History and Culture

The characteristics of Bàu Trúc align closely with many other Cham villages and towns in Ninh Thuận province. While large old-growth trees are scarce, rice fields abound thanks to an intricate irrigation network. These settlements typically follow matrilocalism, with families residing in close proximity often belonging to the same kinship network. Upon passing, the deceased are interred in a traditional grave site known as a ‘kut.’ Presently, there exist 13 clan groups, each consisting of 50 to 60 families. Land ownership is often collective, entailing shared rights and responsibilities, including the maintenance of ancestral grave sites and clan-associated shrines. Houses are constructed in accordance with customary regulations (adat), governing the placement of buildings. Within a single family complex, one might find various structures, including a ‘sang yé’ (customary house), one or two ‘sang mayau’ (two-story houses), a ‘sang tuai’ (guest house), one or two ‘sang gar’ (single-story, horizontal houses), and a ‘sang ging’ (kitchen). In addition, each development includes an eastern well and a southeastern vegetable garden. However, since 2005, these traditionally oriented housing developments have gradually given way to new houses that follow Vietnamese adaptations of European modernist architecture.

The Timeless Artistry of Cham Pottery: Insights into Bàu Trúc’s Methods

As previously mentioned, the villagers hold the belief that Bàu Trúc, a historical figure from the 12th and 13th centuries, ascended to divine status and bestowed the art of pottery upon them. However, extensive research conducted by art historians, historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists sheds light on the fact that many aspects of the pottery techniques practiced in Bàu Trúc bear traces of earlier Champa methods, possibly even dating back to the pre-Champa Sa Huỳnh culture, which thrived around 3000 BP. Elements such as the shared production processes, vessel types, and outdoor pottery firing methods can be traced to Sa Huỳnh archaeological sites. This has led some scholars to suggest that the practices employed in Bàu Trúc may indeed be the oldest in Southeast Asia. While this assertion awaits further comparative verification, it is reasonably safe to assert that Bàu Trúc stands as the oldest extant pottery production center in Vietnam today.

Unlike older production sites that have transitioned away from traditional methods, Bàu Trúc continues to create pottery using straightforward materials. The essential ingredients include clay, sand, firewood, straw, and rice husks for firing. The sand, combined with clay sourced from the nearby Quao River (located 3 kilometers northwest), contains lithium particles, collected during the flooding season from nearby streams and rivers. What makes this particular clay source exceptional is its remarkable adhesive quality and a seemingly inexhaustible supply. Villagers extract clay sparingly, allowing it to naturally regenerate every six months with the ebb and flow of the flooding cycles. To collect the clay, potters dig holes measuring 0.5-0.7 meters in depth, spanning an area of 1 square meter. After harvesting the clay, the hole is refilled, and rice can be planted in the same spot. Within another six months, a fresh supply of clay is ready for harvesting.

Quao River: A Lifeline of Clay for Cham Pottery

Quao River: A Lifeline of Clay for Cham Pottery

The Quao River, nestled in the heart of Central Vietnam, holds a special place in the region’s cultural and artistic heritage. While not as renowned as some of Vietnam’s larger waterways, the Quao River plays a vital role in sustaining the time-honored tradition of Cham pottery, particularly in the village of Palei Hamu Craok (commonly referred to as Bàu Trúc).

A Clay-Rich Lifeline: At the heart of the Quao River’s significance lies its unique clay deposits. The clay sourced from the banks and bed of the Quao River is not ordinary; it contains lithium particles and exhibits exceptional adhesive properties. This clay, often referred to as the “lifeblood” of Cham pottery, is a primary raw material for crafting exquisite ceramic pieces. Its high degree of adhesion ensures that the pottery remains sturdy and resilient once fired.

Cultural and Artistic Significance: The Quao River’s clay deposits have been a cornerstone of Cham pottery production for generations. Cham pottery is a celebrated art form known for its intricate designs and traditional craftsmanship. It holds a special place in the cultural identity of the Cham people and the broader Vietnamese heritage.

Sustaining Tradition: The river’s clay has been instrumental in preserving the time-honored techniques of pottery-making in the region. The villagers of Palei Hamu Craok, whose livelihoods are intricately tied to pottery, rely on the Quao River’s clay to create their exquisite pieces. This connection between the river and pottery has helped sustain a tradition that dates back centuries.

Cultural Exchange: The Quao River’s clay has not only served as a vital resource for local artisans but has also played a role in cultural exchange. In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in Cham pottery, both within Vietnam and internationally. The unique clay from the Quao River has found its way into the hands of artists and collectors around the world, contributing to the global appreciation of this remarkable art form.

Preserving Heritage: Efforts to conserve the Quao River’s clay deposits and the surrounding ecosystem are critical to preserving the rich heritage of Cham pottery. Sustainable clay harvesting practices, coupled with environmental conservation, ensure that future generations can continue to create and appreciate the beauty of Cham ceramics.

The collected clay undergoes a meticulous process that includes drying, followed by a 12-hour soak in water within a pit. Subsequently, the clay is mixed with sand at a 1:1 ratio. The potter then employs their feet and hands to knead the clay, a process known as ‘juak halan,’ until it achieves the desired plasticity. While minimalistic hand tools come into play, they are all traditionally crafted implements. These tools include a large bamboo loop for shaping the glossy raw clay (‘kagoh’), a smaller bamboo loop for thinning the clay body (‘tanuk’), a knife for cutting and etching decorative patterns (‘dhaong’), a stick for puncturing holes in the clay (‘tanay’), a small cloth for smoothing the wet clay surface (‘tanaik’), and a comb for creating wave patterns (‘tathi’). These tools are employed throughout four distinct stages:

- Primary Form Creation (padang gaok): In this stage, the clay is molded into a ‘pumpkin’ shape (‘kaduk’) and placed on a clay ‘anvil’ (‘taok jek’). The potter commences by using their hands to craft the basic shape of the ceramic piece, typically 20-30 centimeters in height. Subsequently, they expand the shape, connecting the base and working their way upwards. The ‘kagoh’ is employed to smooth out any imperfections and fingerprints, resulting in a sleek surface, which is further refined by using the cloth (‘tanaik’) to achieve a glossy finish.

- Smoothing the Piece (tanaik uak gaok): During this stage, potters employ the ‘tanaik’ by wrapping it around their hand, lightly dampening it with water, and repeatedly rubbing it over the piece’s body. This technique is utilized to create a bell-shaped or cupped mouth, with a standing rib, encircling the entire exterior lip of the piece.

- Adding Decorative Motifs (ngap bingu hala): At this juncture, various motifs are introduced using methods ranging from cloth impressions to seashells, plant flowers, leaves, and shells. Traditional motifs encompass jagged, sharp lines, waves, vegetation patterns, and an array of sea-inspired designs. In response to market demands, these patterns have evolved in sophistication over the past decade, incorporating human and animal motifs in accordance with classical Champa art styles.

- Final Stage (kuah gaok): Following decoration, the pieces are left on a forming platform to dry before being relocated to a shaded area to prevent cracking. Once thoroughly dry, the potter employs a ‘tanuh’ to remove the ceramic from the platform, signaling the commencement of the firing stage.

Cham pottery follows a distinctive tradition that eschews kilns, opting instead for outdoor firing. Materials used for firing include wood gathered from the forest during the dry season, alongside straw and rice husks collected from rice fields after harvest. The pots are methodically stacked by size, with the largest items forming the base and the smallest atop, culminating in a colossal cube structure. The pottery is then enveloped by slabs of extremely dry wood, measuring 20-30 centimeters in height. This arrangement is subsequently covered with a blend of straw and husks. The husks facilitate ignition, while straw ensures consistent burning, resulting in a rapid, hot, and sustained burn lasting approximately two to three hours. After firing, if desired, a natural, plant-based glaze can be applied to the pieces for additional decorative flair.

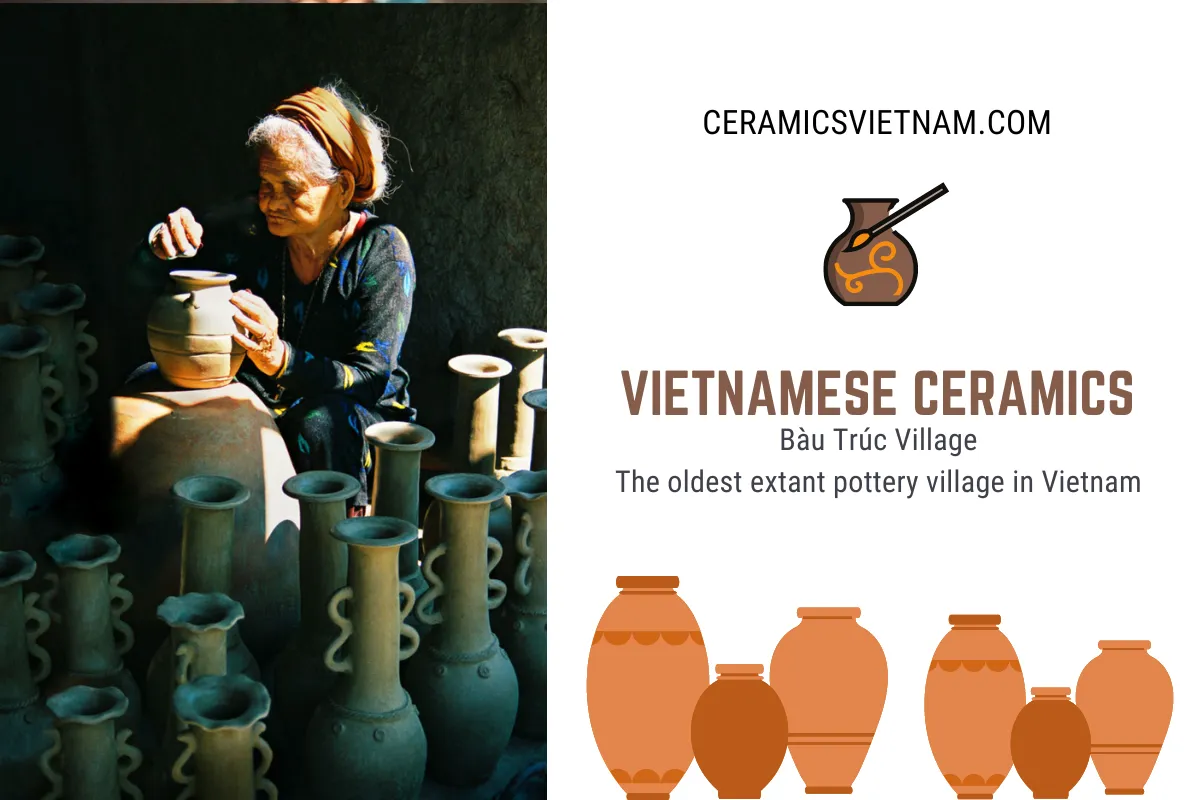

Artisans work the clay predominantly by hand

The production process, rooted in age-old traditions, remains virtually unchanged over time. From clay preparation and gathering to shaping and firing, potters rely solely on their manual dexterity, aided only by a modest selection of hand tools. A Bàu Trúc potter’s expertise is honed through years of training, enabling them to adeptly navigate each stage of production year after year, carrying forward a tradition that remains timeless in its craftsmanship.

Artistic Evolution: Contemporary Styles and Forms in Bàu Trúc Pottery

The pottery produced in Bàu Trúc Village can be broadly categorized into five distinct groups, each distinguished by its unique style and functional purpose. These categories provide insight into the diversity and versatility of Cham pottery.

- Large and Small Cooking Pots (gaok praong and gaok asit): These pots are primarily used for cooking food or storing drinking water. They feature round bottoms, small mouths, and relatively large round bodies. Typically, they stand at least 20cm tall, with an average base diameter of 15cm and a mouth diameter of approximately 5cm. The walls of these pots are generally around 0.8cm thick.

- Klait or Glah Pots: Characterized by a full bell mouth, short neck, drooping shoulders that flow downward, and a full middle body with a smaller round bottom, these pots are primarily used for cooking and are of standard size. They typically measure 20cm in height, with a 10cm mouth diameter and walls averaging 1cm in thickness.

- Jek and Khang Pots: These pots find diverse applications, serving as containers for various substances, including water, salt, and rice. They exhibit a slightly rounded bottom, a standing cupped mouth, a standing neck, sloping shoulders, and a round body. Most often, they are 40cm tall, possess a 15cm mouth diameter, and feature even thicker walls, generally measuring 1.2cm in thickness.

- Utility Pots with Straps: This category encompasses pots that may have straps attached and often feature two to three ‘legs.’ They boast full cupped mouths and flat bottoms and are primarily utilized as portable stoves (‘wan laow buh njuh’) or braziers (‘wan laow dhan’) on which cooking pots can be heated. These pots are typically shallow and include individual water storage pots (‘kadhi’).

- Decorative Pieces and Toys: These pieces are purely ornamental and may take the form of animals or include animal motifs, such as water buffalo (‘kabaw’), cattle (‘limaow’), humans (‘manuis’), and trumpet-like instruments (‘halan padet’). They are often designed for children or as home decor.

Historically, the first three categories dominated production. However, in the past two decades, notable shifts have occurred. To meet growing production demands, an increasing number of men have entered the traditionally female-dominated pottery profession. Moreover, while small cooking pots (‘gaok gom’ or ‘klait’) and large water storage pots (‘buk’) were once the most common products, there has been a surge in the production of decorative pieces and toys. These pieces are gradually merging with the traditional categories, as even the ‘traditional’ pots are becoming more intricate.

The pottery produced in Bàu Trúc can be broadly categorized into five distinct groups

The contemporary pottery landscape in Bàu Trúc is marked by a dynamic blend of styles and forms. In response to market trends, pottery artisans have diversified their offerings to include flower vases, variations of water pots, light fixtures, and statues inspired by classical Champa deities such as Shiva and Nandin, Brahma, Vishnu, and Apsara dancers. These innovative designs not only cater to niche markets but also reflect the growing connection of artisans to classical Champa art. Many of these new creations are the brainchild of a younger generation of artisans who have gained popularity in urban areas across southern Vietnam. Their works now adorn homes, cafes, restaurants, hotels, and seaside resorts.

The appeal of Bàu Trúc pottery has transcended national borders, with regular shipments of these unique creations finding international destinations in the 2010s. The centuries-old tradition of Cham pottery, guided by the inspiration of the deity Bàu Trúc, stands as an intangible heritage cherished by the global community.

Read more

Leave a reply