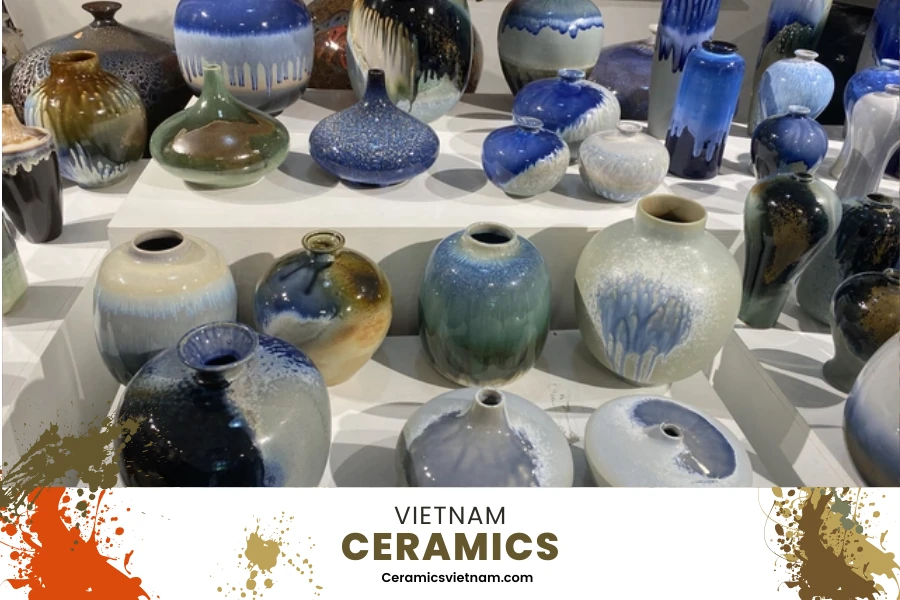

Bat Trang Ceramics is the general term for various types of Vietnamese ceramics produced in the village of Bat Trang, located in Bat Trang commune, Gia Lam district, Hanoi.[1][2] In Sino-Vietnamese terms, the character “Bát” (鉢) refers to the monk’s eating bowl (in Pali, it is called Patra), and “Tràng” (場, also pronounced as “Trường”) means “a large yard” or a specialized area.[3] Thus, the name Bat Trang can be understood as “a large yard specializing in the production of bowls.” However, according to some other sources, the name Bat Trang may originate from the name “Bạch Thổ Phường,” meaning “the district of white clay.”

Bat Trang ceramics are exported to many countries, including Japan, South Korea, Europe, the United States, and many others[4]. Bat Trang has become a famous tourist destination, attracting visitors from both domestic and international locations for sightseeing, shopping, and experiencing pottery making[5][6][7]. On December 20, 2019, the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism of Vietnam announced that the pottery craft in Bat Trang village is a national intangible cultural heritage.

Let’s learn with CeramicsVietNam about the typical glaze lines for making Bat Trang ceramics.

Location of Bat Trang pottery village

The commune of Bat Trang (社鉢場) consists of two hamlets, Bat Trang and Giang Cao, located in Gia Lam district, Hanoi city. Formerly part of Bac Ninh province, it became a suburb of Hanoi in 1961. The Bat Trang village was established when the Ly dynasty relocated the capital from Hoa Lu to Thang Long[13]. The inhabitants of Bo Bat village (in Bo Xuyen commune and Bach Bat hamlet within Bach Bat township, Yen Mo district, Truong Yen phu, Thanh Hoa trấn, which is now two hamlets in Yen Thanh commune, Yen Mo district, Ninh Binh province) moved to this village as per King Ly Cong Uan’s decision to relocate the capital closer to Thang Long.

Typical glaze lines for making Bat Trang ceramics

Bat Trang ceramics has 5 characteristic glaze lines expressed through each different period to create different characteristic products: blue glaze initially appeared in Bat Trang with ceramics ranging from lead blue to dark black; Brown enamel is presented in a traditional style and painted using blue enamel technique; Ivory white enamel was used on many types of ceramics from the 17th to the 19th century. This enamel is thin, ivory yellow, and glossy, suitable for meticulous embossed decorations; Celadon was used in combination with ivory and brown enamel to create a very unique Tam Thai style of Bat Trang in the 16th and 17th centuries, and cracked enamel is a type of enamel that only appeared in Bat Trang from the late 16th century and developed continuously. continued through the 17th–19th centuries.

Lam Glaze ( Men lam )

Typical glaze lines for making Bat Trang ceramics

This is the earliest type of glaze used in Bat Trang since the 14th century. Lam glaze is ceramic glaze combined with cobalt oxide to achieve its base color. Bat Trang artisans utilized lam glaze alongside the brush-painting technique on ceramic pieces. Unlike brown glaze, lam glaze is always covered with a glossy white glaze, highly vitrified after firing. Lam glaze ranges in color from blue-gray to dark blue. Despite some similarities with the flower glaze pottery produced in the Chu Dau kiln (Hai Duong), Bat Trang’s flower glaze in its early period had distinct characteristics in both form and decorative patterns. Bowls, plates, vases, and lamp bases with flower glaze from Bat Trang in the 14th-15th century are recognizable for their freehand painting style, whether depicting landscapes, floral patterns, or dragons.

In the 16th century, Bat Trang flower glaze turned into a dark blue shade. Lam glaze was used to paint clouds, combined with raised dragon decorations on raw clay, depicting lotus petals, decorative bands, and pairs of lamp bases. Lam glaze was also used to paint raised dragon, floral, and lotus petal motifs on lamp bases and incense burners.

The 17th century saw limited development in lam glaze at Bat Trang. Some existing pottery pieces from this period, such as lamp bases, incense burners, and jars, exhibit areas where the brown glaze decoration, applied over the white glaze, has peeled off, revealing greenish-brown shades. Despite the lack of refinement in lam glaze drawings and common issues of smudged patterns, the raised carvings remain intricate and reach a peak in craftsmanship.

At the end of the 18th century, during the height of crackle glaze development, Bat Trang introduced a combination of relief decoration with blue painting on lamp bases, reviving the use of lam glaze on Bat Trang ceramics.

In the 19th century, lam glaze was used for decorative painting on incense burners, candle holders, vases, bowls, and altar vessels, with crackle glaze covering in ivory white or at the ceramic’s peak. The characteristic features of Bat Trang’s lam glaze are subdued colors and painting styles, generally leaning towards a darker palette. Lam glaze was successfully employed to depict landscapes, buildings, castles, and characters on ceramic vessels. The vibrant lam glaze was applied to decorate the pot’s rim, creating some of the most beautiful flower glaze ceramic models from Bat Trang in the late 19th century.

Amid the trend of influencing styles, themes, and market competition with Chinese porcelain, 19th-century Bat Trang ceramics experimented with multiple glaze colors. For instance, to depict the theme of Bat Tien crossing the sea, Bat Trang artisans used brown and lam glazes to paint the decorative patterns on the pot, followed by a white crackle glaze. Lam glaze, alongside brown glaze, was employed to paint willow branches, orchids, and grass in the raised picture of To Vu herding goats. The combination of dark and light shades of brown and lam glazes resulted in an impressive multicolored ceramic peak. This serves as vivid evidence of the skilled hands passed down through generations of Bat Trang artisans, continually evolving and advancing.

Brown Glaze ( Men nâu )

Typical glaze lines for making Bat Trang ceramics

One of the earliest glazes used in Bat Trang is the brown glaze. The color intensity of this glaze depends largely on the ceramic bone (Bat Trang ceramic bones are thick and often have a gray-brown color). In ceramics dating back to the 14th to early 15th century, brown glaze was applied to decorative items in conjunction with a white ivory background glaze. This includes items such as lamp bases, towers, pots, cups, and plates. The brown glaze has a reddish-brown hue, often referred to as chocolate color, and it lacks luster. The surface of the glaze typically exhibits a rough texture.

During the 14th century, Bat Trang ceramic artisans learned to limit the influence of the brown glaze on the ceramic by painting it on a layer of white ivory glaze. This technique transformed the reddish-brown glaze into a golden-brown hue.

In the various types of ceramics from the 16th to 17th centuries, the brown glaze was often combined with jade glaze and ivory white glaze, creating different shades. The brown glaze was used to outline bands, paint lotus flowers or dragon motifs, and was applied to rectangular incense burners.

Throughout the 18th century, brown glaze continued to be extensively used in a traditional manner. Some artisans experimented to enhance the richness of this glaze, particularly in the creation of a pair of tiger statues crafted around 1740. The brown glaze under a crackled glaze layer produced a tiger skin with a more diverse range of colors.

In the 19th century, brown glaze served as a background for white and green glaze decorations. Vases and crackled ivory glaze jars depicted various decorative themes such as “Prosperous Fisherman,” pine and crane motifs, Tô Vũ herding goats, and “Eight Fairies Crossing the Sea.” Brown glaze was used to paint tree trunks, willow trees, or added details to clouds and the hems of clothing for the “Eight Fairies.” The 19th century marked the transition of brown glaze into a glossy glaze (often referred to as mottled glaze), which has been widely used in Bat Trang ceramics to this day.

Ivory White Glaze ( Men trắng( ngà ))

Typical glaze lines for making Bat Trang ceramics

This is a type of ivory white glaze, often taking on a yellowish ivory hue when fired at high temperatures, but sometimes appearing in grayish-white or milky-white tones, and occasionally translucent. Alongside the shapes and decorations, the ivory white glaze contributes to the distinctive character of Bat Trang ceramics. Ivory white glaze has been used to overlay decorations on both jade and brown glazes, but in many instances of Bat Trang ceramics, only ivory white glaze is utilized.

In the 17th century, Bat Trang ceramics reached its pinnacle in the technique of raised decoration, employing various techniques such as carving, embossing, and assembling. Ivory white glaze was applied to incense burners to cover the edges, mouths, and outer edges of raised decorations, rarely extending to cover the decorative motifs. Due to the thinness of the ivory white glaze, refined ceramic bones, and high firing temperatures, the quality was excellent. However, some products with thicker applications of ivory white glaze on raised decorations still exhibited crack lines in the glaze.

In the 18th century, ivory white glaze was still used on various forms alongside raised decorations. Round incense burners with raised dragon and moon motifs, for example, had the remaining parts covered in ivory white glaze.

Entering the 19th century, Bat Trang ceramics had not entirely abandoned the raised decoration style. Ivory white glaze was still used on items such as vases, jars, incense burners, and round statues. Vases with lids featuring raised cloud and treasure dragon motifs, where the remaining portions were covered in ivory white glaze, exemplify this style. Other items, like pine-handle incense burners and “Thọ” character incense burners, as well as pairs of monkey head and snake body statues, architectural dragon statues, three-headed statues, and statues of Quan Am Bodhisattva seated on a lotus, all continued to use ivory white glaze, sometimes combined with gray glaze.

Jade Glaze ( Men rạn )

Typical glaze lines for making Bat Trang ceramics

From the 14th to the 19th century, jade glaze was prominently used alongside ivory white and brown glazes. Jade glaze, along with ivory white and brown glazes, contributed to the unique Tri-color style of Bat Trang ceramics in the 16th-17th centuries. On lamp bases adorned with jade glaze, raised lotus blossoms, circular bands of lotus petals, wheel-shaped flower motifs, dragon motifs, and raised floral patterns along the edges were painted.

Jade glaze was also utilized to depict clouds, adorn various sections of decorative patterns, bases, and vertical columns of dragon-shaped incense burners. A dark moss-like glaze was applied to square columns resembling two-story houses or certain rectangular decorative patterns on rectangular incense burners. Jade glaze, with its light hue, was used on lamp bases and lotus-shaped incense burners. On round incense burners with jade glaze, four S-shaped motifs were often painted in the middle of the body and the base, along with a pair of similar motifs on the abdomen. Dark jade glaze was also applied to some raised decorative patterns, the image of dragons on round incense burners, and on the raised decorative pattern along the front of the pedestal of the statue of a dragon.

Although appearing in various shades, the presence of jade glaze holds great significance as it is only found on Bat Trang ceramics from the 16th to the 17th century. This could be considered strong evidence for dating various types of Bat Trang ceramics from this period.

Inscriptions (Minh Văn)

Bat Trang ceramics often feature inscriptions, expressed through engraved or written characters using lam glaze beneath the ivory white glaze. Some inscriptions clearly indicate the production year, full name, hometown of the creator, along with the name and sometimes even the title of the person commissioning the work.

In the 15th century, an inscription carved on the lower part of a lamp base reads: “Thuận An Phủ, Gia Lâm district, Bat Trang commune, loyal servant Hoàng Li province Nguyễn Thị Bảo.” On a brown-glazed belt in the middle of the lamp base, six Han characters written in lam glaze state: “Created by Hoàng Phúc, Thời Trung commune.” Another inscription on the lower part of a lamp base reveals: “Artists: Vũ Ngộ Trên, Bùi Thị Đỗ, Hoàng Thị Vệ, Bùi Huệ, and Trần Thị Ngọ; Creation period: Diên Thành era.” Some inscriptions even specify the person commissioning the work, like a pair of lamp bases with inscriptions stating: “Commissioned by Lê Thị Lộc from Vân Hoạch, Xuân Canh district, Đông Ngạn.” Creation period: The 2nd year of Diên Thành. Another pair of lamp bases has a lengthy inscription, with one side having 3 lines and the other 14 lines, indicating: “Artists: Bùi Huệ and Bùi Thị Đỗ; Creation period: November 25th, the 3rd year of Diên Thành; Commissioned by the families of Lưu, Nguyễn, Lê, Đinh, etc. In sorrow, the Lưu family, titled Ninh Dương Bá, works at Thanh Tây vệ, Ti Đô commanding envoy, Đô commanding inspector. Hometown of the Lưu family: Lai Xá commune, Đan Phượng district, Phủ Quốc Oai.”

Many products with inscriptions are displayed in the Vietnam History Museum, some are exhibited in foreign museums, some are owned by antique collectors, some are still in circulation among the public, and some remain buried deep in the ground.

Leave a reply