High-fired ceramics were already being produced in Vietnam by 2,000 years; the white-glazed white-bodied ceramics unearthed from the Thanh-hoa tomb predate any pottery found in China to date.

The Vietnamese became aware of the vitrification process in the 1st century AD, as Chinese artisans followed Chinese soldiers and administrators to establish new settlements in the area of modern Hanoi. However, Vietnamese goods are very similar to Chinese forms.

After the fall of the Han Dynasty in the early 3rd century CE, Vietnam’s early pottery tradition seems to have come to an end. A revival occurred during the Li Dynasty (1009-1225) and received a major boost when the Ming Dynasty severely restricted exports in the late 14th century.

All references are from works listed in the bibliography at the end of this article.

Bat Trang

The Bat Trang Kiln is located about 10 kilometers southeast of Hanoi. The name first appeared in 1352. The first mention of pottery production here dates back to 1435. The site is still active today.

One legend is that it was founded by the Chu Dau people, while local lore holds that three Vietnamese scholars who went to China on a diplomatic mission during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1126) established the might of the Bat Trang Kiln. They are said to have visited a ceramics factory in Guangdong and brought back the technical knowledge that led the people of Bat Trang to learn how to make glazes: a scholar’s white glaze; a second scholar, red glaze; a third scholar, dark yellow glaze; Everyone goes to a different region [Phan Huy Lê, Nguyen Chién & Nguyen Quang Ngoc 1995: 48]. Other evidence points to Thanh Hoa as the ancestor of the Bat Trang industry [Miksic 2009:60].

According to Long [1995:87], Bat-Trang pottery was sent to China as a tribute in the 15th century.

Due to “the internal homogeneity of the utensils and the scarcity of archaeological data” [Brown 1988: 27], there is no chronology of Vietnamese utensils from the 14th to the 17th centuries.

Production of Bat Trang wares likely peaked in the 15th and 16th centuries, coinciding with the Ming Gorge, when exports of Chinese goods were banned. However, modern kilns there have been in continuous operation since at least the 16th century [Brown 1988:32].

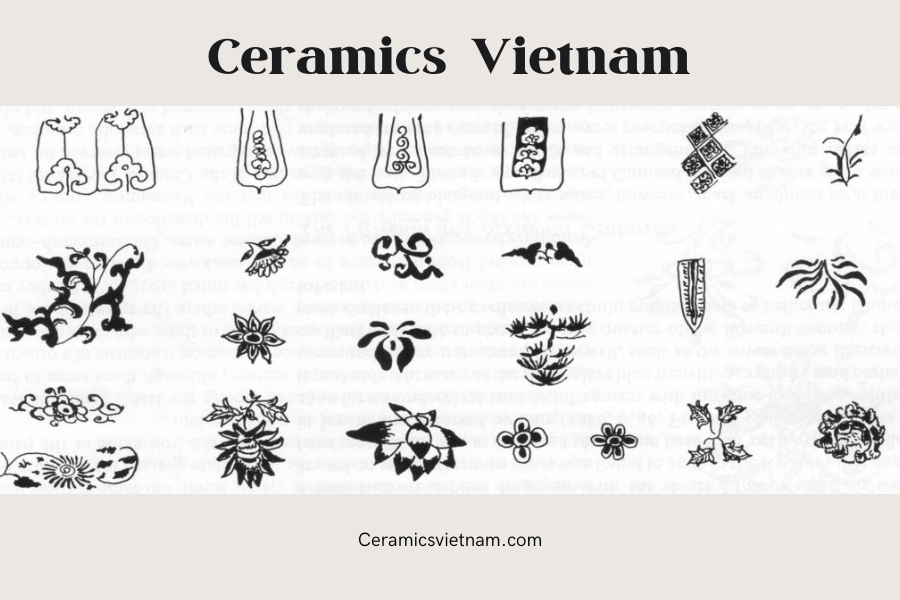

Underglaze blue decorative motifs, 15-16C. (Photo: Brown 1988: fig 17)

Types of designs dated to the early 15C by Robert P. Griffing Jr (1976) (Photo: Brown 1988:fig 18)

Vietnamese pottery of this period is known for its blue and white porcelain. The origin of this method of decoration is uncertain, but it likely coincided with the Ming invasion of North Vietnam in 1407. Brown [1988: 25] tells us that “underglaze iron blacks and solid colors began to disappear rapidly as cobalt was used in underglaze painted decoration”, as well as earlier decorative patterns and forms.

In terms of decoration, there are not only blue and white, but also red and green overglazes, and sometimes yellow.

The designs (top left) can be found in different combinations on large plates and small glasses; these designs (bottom left) often appear as central medallions on large plates.

The new assortment is huge: Bottles, Glasses, Bowls, Plates, Bowls, Jars with Lids, Kendi, Jarlets, Zoomorphic Waterdrops and Miniatures. An example is shown below.

Pouring vessel with moulded heads of twin crested birds which serve as spout, missing cover, with anatomical parts drawn in underglaze blue. 13-14C. H: 7 cm, W: 17 cm. NUS Museum S2002-0002-003-0

Octagonal blue and white jarlet having a putty-coloured biscuit, with underglaze decoration of a lotus leaf collar and panels of a vegetal form alternating with wave patterns. 15C. H: 8.6 cm, D: 9 cm. NUS Museum S1980-0206-001-0

Blue and white ewer with a short, stubby spout; a carved handle in the form of a cloud (probably not functional); and a chocolate base. 16C. H: 22 cm; D: 18 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-006-0

8-lobed moulded blue & white jarlet having a putty-coloured biscuit, with a bright underglaze blue decoration with evidence of heap and pile; decoration of a collar of scalloped petals on the upper shoulder, and on the lower shoulder a band of 4 cloud-scrolls; the body with a scroll comprising 4 peony blossoms. 15C. H: 8.8 cm, D: 9.9 cm. NUS Museum S1967-0014-001-0

Blue and white ewer with an elaborately turned handle and a long teapot-like spout having moulded cloud forms; decorated in blue underglaze throughout; a circle of lotus petals on lid, another on collar; two-thirds of body consists in 4 rounded rectangular panels comprising leaf and flower motif, separated by wave motif; lower body with perfunctory lotus panels; splayed foot with chocolate slip at bottom. 16C. H: 19.5 cm; D: 21 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-004-0

Blue & white kendi with onion-shaped spout and a stout neck that ends with a short flange just below the mouth-rim; decorated in dark blue underglaze on neck and collar, both sections divided by horizontal borders; motif on neck is a stylised leaf motif, and on the collar floral and vegetal scrolls; fluted body and spout with blisters in glazing; wide flat foot with glazed base. Late 15-early 16C. H: 16.6 cm, D: 16 cm. NUS Museum S1955-0242-001-0

Six-sided moulded jarlet with underglaze blue-black decoration; around collar, 6 pentagonal shapes comprising foliage-type motif alternating with geometric designs and on the body, 6 hexagonal panels with similar alternating motifs. 16tC. H: 5.9 cm, D: 7.1 cm. NUS Museum S1972-011-001-0

Jarlet with 4 pierced ring handles around the neck, in underglaze blue decoration of large flower blossoms amidst foliage. The yellowish-white glaze is crackled. 17C. H: 9.1 cm, D: 11.2 cm. NUS Museum S1955-0179-001-0

Elephant-shaped ewer, the tail forming a handle and the trunk a spout. The anatomical parts and decorations of florettes are in blue underglaze with evidence of heap and pile. Similar elephants have been found in the Philippines (see Gotuaco, Tan, and Diem 1997: 252, plate V28). 15-16C. H: 17.5 cm, W: 11 cm, L: 21.5 cm. Private collection

Plate with an unglazed rim, the flat lip decorated with a classic scroll, the cavetto with 6 stylised lotuses in a scroll; the centre medallion with an elaborate peony wreath surrounded by a scalloped- petal border; the outside wall with 16 lotus panels enclosing leaf-forms. This dish may be roughly dated to the mid-15th century on the basis of a bottle in the Topkapi Museum bearing a date corresponding to the year 1450. 15-16C. H: 6.3 cm, D: 37.5 cm. NUS Museum S1969-0067-001-0

Deep bowl with décor in blue underglaze; a floral medallion within a circular border; similar motifs interspersed on cavetto with a cloud scroll along inside rim; exterior wall divided into two horizontal registers; the upper of peony blooms and vegetal scrolls; the lower of lotus panels; high carved foot with chocolate slip on base exterior and interior. For an even larger example (30.2 cm in diameter) found on the Pandanan shipwreck in the Philippines, see Gotuaco, Tan & Diem 1997: 226–227, plate V4. 15. H: 13.5 cm, D: 24.7 cm. Private collection

Cream and green-glazed limepot with a moulded and incised handle in the form of a vine. (See also Brown 1988: pl. XIV a). 17-18C. H: 16 cm; D: 13 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-050-0

Blue and white limepot with decoration of stylized leaf and floral motifs. 18tC. H: 20 cm; D: 16.5 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-054-0

Blue & white dish with underglaze bamboo motif, unglazed rim with classic scrolls, plantain leaves on the cavetto and the outside wall having 11 lotus panels enclosing leaf forms; no chocolate base but a slightly greenish glaze. 15-16C. D: 35.8 cm; H: 7.5 cm. NUS Museum S1971-0056-001-0

Plate with fish motif on centre medallion, the cavetto decorated with 5 feathery leaf-like motifs; lotus panels in underglaze blue on exterior walls, high foot with two horizontal bands near base; chocolate base. 16C. H: 9 cm, D: 33.5 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-044-0

Dish with an unglazed rim, the flat lip with a classic scroll, the cavetto with a scroll of 6 flowers, the centre medallion with a lotus wreath surrounded by a border containing cloud-scrolls, the outside wall with 11 lotus panels enclosing leaf-forms, all painted in a pale blackish underglaze blue. The carved foot is unglazed, and has a chocolate base. 16-17C. H: 8 cm, D: 36.2 cm. NUS Museum S1955-0260-001-0

Polychrome plate decorated in underglaze blue with red and green enamel; a tiger on centre medallion surrounded by cloud motifs and a circular border of scallop motifs; on cavetto, six ogival panels of flower blooms on a wave background. 15-16C. H: 9.5cm, D: 41.5 c Private collection

Tall octagonal jar with 8 handles; neck decorated with lotus panels in blue underglaze; multi-coloured overglaze enamels of 2 dragons, with pearl and 8 auspicious objects on a background of cloud and wave motifs; near foot, floral scrolls in blue underglaze. 17-18C. H: 34 cm, D: 27 cm. NUS Museum S1980-0001-001-0

Blue & white jar with an unglazed rim (probably had a lid); décor in blue underglaze with heap and pile, divided into three registers by 3 horizontal bands; collar with stylised cloud motif; body with floral and vegetal scrolls; lower body in lotus panels. 16C. H: 21 cm; D: 16 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-007-0

Tall jar of ovoid shape with 4 handles with moulded florettes, crackled glazed; underglaze blue decoration of classic scrolls on neck; on body, large flower blooms on a floral background; and around base, floral scrolls. (See also Brown 1988: pl. Xlla). 17C. H: 29.7 cm, D: 25.4 cm. NUS Museum S1955-0174-001-0

Blue and white bottle of yü hu chun ping shape, the neck decorated with 4 upright plantain leaves, the shoulder with 4 lotus-panels with leaf forms, and the body with 4 panels comprising vegetal motifs on a wave background; lower body with lotus panels; foot-rim entirely restored. Late 15-early 16C. H: 27.5 cm, D: 15.5 cm. NUS Museum S1969-0110-001-0

Rectangular incense burner with ivory and moss-green glaze, Le Dynasty, 1637. The milky or ivory white glaze was applied on the corners and borders but not on the decorations, and the ceramic form are both typical of the kiln site and period. Eleven such incense burners with inscriptions of the 17th century are known. Greyish-blue and yellowish-brown glaze were used on censers made by the potter Dang Huyen Thon in the late 16th century. The three-part structure of the larger incense burner in the collection is similar to that of an inscribed artefact in Vietnam dated 1637 (Nguyen 1999: 167). Ornately decorated with phoenix dragons made from sprig designs. (See also Nguyen 1999: 167, pl. 51, N81; Phan Huy Lê et al 2004: pls. 61, 86-91.) 17C. H: 34 cm; D: 24 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-045-0

Bat Trang was also famous for making incense burners (pictured left) in the 16th and 17th centuries. The mass production of these incense burners is a good testament to the revival of Buddhism during this period [Miksic 2009: 61].

Finally, the potters at Bat Trang consisted of men and women, sometimes husbands and wives. This shows the tradition of potters signing some of their pieces, as at Chu Dau.

Chu Dau

Chu Dau was discovered in 1983 in the Nam Sach district east of Hanoi, where a series of excavations took place between 1986 and 1991. Production is estimated to have begun in the 13th century, peaked in the 15th century, and declined in the 16th and 17th centuries.

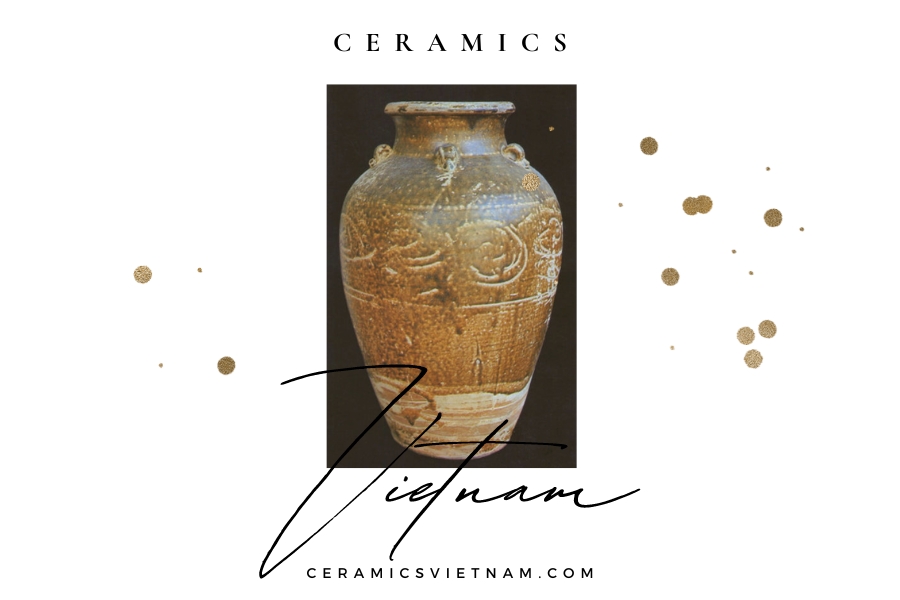

Chu Dau is mentioned in the famous vase (left), signed by a lady named Bui, dated 1450, and housed in the Topkapi Sarayi Museum in Istanbul.

In the late 16th century, another potter, this time a man named Dang Huyen Thong, signed at least ten of his works, including incense burners and candlesticks. He is unusual in that he is both a BA and a potter. His home was only two kilometers from Bamboo Island (Tang 1993: 34).

Zhu Dao Kiln produced a wide variety of shapes and decorations. These included oddities such as goblets, beauty bottles, lime jars, double gourd jugs with elaborate handles and spouts, and jars with lids, although the vast majority of products were bowls, many with chocolate wrappers on the bottom. Decoration includes celadon glaze, cobalt blue design, overglaze, and brown glazed bowl with carved motifs.

Unfortunately, there is not much left of the oven itself. However, much furnace furniture and many saggers have survived. A ring bracket with three spurs was also found.

The famous vase from the Topkapi Museum, Istanbul. H: 54 cm.

Additional information for the three sections on the right:

Top: D: 4 cm, H: 2 cm; ACM HC SEA 011 — Exterior decorated with a horizontal band of lotus petals between 2 lines; interior grey-green glaze with visible pooling in well; rim and recessed base unglazed.

Middle: D: 5.6 cm, H: 2.5 cm; ACM HC SEA 010 — Moulded form corresponding to decorative panels of alternating designs comprising four-petaled flowers and leaf scrolls; all in blue underglaze; a fine grey-green glaze in interior; rim and recessed base unglazed.

Bottom: D: 6.4 cm, H: 3cm; ACM HC SEA 009. — Exterior decorated in bright blue underglaze of 4 visible panels of alternating wave and leaf scroll motifs; panels separated by vertical lines; around base, 3 horizontal bands in blue-green underglaze; rim unglazed; interior with a grey-green glaze with slight pooling in well; unglazed recessed base.

Go-Sanh

Go-Sanh, literally “Potter’s Mountain”, is located in Binh Dinh Province in central Vietnam. Before modern times, it was the empire of the Chams, a Malay-Polynesian-speaking group who founded many important kingdoms and were a fearsome place for the Khmer and Vietnamese before their gradual conquest in the 15th century. enemy.

Go-Sanh pottery is divided into three groups: The first group (1) consists of saucers with green or blue-gray glazes, with unglazed stacked rings on the inner bottom, as shown in the first example below. The grayish tone of the unglazed interior, which occurs on both such vessels and the celadon, also helps to identify this work as belonging to the kiln site.

A celadon bowl belonging to the second category (2), similar in tone to the above, can be seen on the unglazed base of this cup-shaped bowl. The celadon glaze has eroded over time, but some color can still be seen from the glaze build-up on the uneven surface. The final third (3) consists of brown glazed vessels of various shapes, often with an orange to reddish brown hue. This shade is surprisingly light and can be seen in the unglazed lower half of the Binh Dinh jarlet pictured below.

The final category comprises obrown-glazed vessels of various shapes that tend to exhibit an orangey to reddish-brown clay. This clay is surprisingly light in weight and can be seen on the unglazed bottom half of the jarlet from Binh Dinh shown below.

Go-Sanh. 15 C (or earlier) H: 7.2 cm; D: 11.8 cm. NUS Museum S1966-0007-001-0

Go-Sanh beaker-shaped cup with a runny mottled green glaze with bubbles that are caused by over-firing. (See also Brown 1988: pl. 22b). 14-15C. H: 7.7 cm, D: 7.7 cm. NUS Museum 1980-0330-001-0

The brown glaze on this jarlet from Binh Dinh has mostly flaked off, but a grey slip is visible beneath it. 14-15C. H: 8 cm, D: 8 cm. NUS Museum S1980-0161-001-0

Jarlet from the Binh Dinh kilns with two incised decorative circular bands on the shoulder, covered in a caramel-coloured glaze. The lower body and carved foot are unglazed, with an ochre-coloured biscuit. (See also Brown 1988: pl. 23c). 14-15C. H: 8.6 cm, D: 9.2 cm. NUS Museum S1968-0056-001-0

Jar with reddish-orange body, the decoration incised through a runny mottled green-brown glaze. H: 42 cm. Collection of Ha Duc Can. (Photo source: Brown 1988: pl. XV b). Decoration is generally rare on Binh Dinh wares, except for large brown-glazed storage jars which sometimes have incised or moulded appliqué motifs.

Jar with five long scaly dragons whose necks form handles, incised decoration of waves under the glaze, a reddish body, and a thin, runny, golden brown glaze speckled with pinholes. From the hill tribes, Binh Dinh province. 14-15C. H: 42 cm. Collection of Ha Duc Can. (Photo source: Brown 1988: pl. 22c)

Pear-shaped bottle from Binh Dinh with a flaring mouth-rim, a dark olive-green glaze, and horizontal incised lines on the body. The unglazed lower body and foot show a light brick-coloured biscuit. 14-15C. H: 23 cm; D: 11 cm. NUS Museum 1969-0123-001-0

Thanh Hoa

From the Han Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty (111-979 AD), North Vietnam was conquered by the Chinese, who ruled as far as Thanh Hoa (about 150 km south of Hanoi). 1407-1427 is the second period of Chinese rule.

Thanh Hoa was excavated in the 1920-30s due to public works in France. Funeral objects dating from the 1st to 3rd centuries and the 10th to 13th centuries were found, roughly contemporaneous with the Han and Song Dynasties in late China. These are known as Thanh Hoa vessels and are considered uniquely Vietnamese rather than Chinese. The first exhibition of these handicrafts was held at the Musée Guimet in Paris in 1931.

Beginning in 1925, the area was heavily looted, prompting the authorities to enact laws against illegal excavations. Unfortunately, this hasn’t stopped amateur collectors from building large collections. Poor recordkeeping for everyone—prospectors, looters, and collectors—is also an ongoing problem.

In the early stages of excavations, no kiln sites for glazed porcelain were found, only 20 crusader kilns (the source of unglazed, reddish, high-fired porcelain). There is no kiln with paste body or greenish glaze white body in Han Dynasty.

Thanh Hoa ware, found at these burial sites, is divided into two groups:

- (1) The first, according to Roxanna Brown [1988: 17], is classified as the “Later Han period”, ranging from the 1st to the 3rd century AD, and is “vessels of white lumps and milky white to greenish glaze”” ’ Miksic [2009: 58] tells us that Bat-trang, then 10 km north of Hanoi, was the only known mid-16th century kiln site in North Vietnam. However, it is known that high-fired ceramics were produced in Vietnam 2,000 years ago. The white-glazed and white-bodied pottery unearthed from Qinghua Tomb was earlier than any pottery known in China at that time.

- Han Dynasty pottery was made of reddish-brown or pale yellow clay and painted with a matte green glaze. However, the shapes are very similar to those in China. “

Unglazed house model with a flat base, reddish body and removable roof. 1-3C. L: 27.5 cm. Saigon National Museum. (Photo source: Brown 1988: pl. I a)

- (2) The second period is what Brown refers to as the “Lee dynasty”, roughly corresponding to their reign 1009-1225, ie 10th-13th centuries. This is a moment of great pride for the Vietnamese, successfully breaking away from Chinese authority. Many also see this as an artistic renaissance when trade resumed. Between the first and second periods is the intermediate period from the 4th century to the 10th century, but few finds can be definitively attributed to this period.

- The utensils of the Li Dynasty are mainly covered urns, mostly unglazed, dark gray, white to gray utensils. The latter is available in the following glaze types: iron brown inlay, light green ochre, white, black and brown monochrome. There are also two types of celadon: thin, light, and translucent; the other is thick and dark. Finally, there are vessels decorated with underglaze black [Brown 1988: 17].

- Decorative inlays are found in the earliest Li Dynasty vessels. These forms are limited to “covered urns, some with hollow feet”, such as the example (top right), which may have lost its cover. Other forms, Brown tells us, “include tall cylindrical cylinders, wide basins, and low jars with flared rims. [These] ornaments are carved with broad scratches in outline, and the interior space is glazed in brown. Then the rest of the vessel Apply a glaze that is usually liquid, clear, or greenish in color. In some rare instances, this color scheme is reversed… Occasionally a thin layer of white glaze is visible under the glaze. The bottom is always unglazed and Mostly flat, the sherds are white or light gray in color. The decorative designs are mostly vegetal, with tendrils and simple flowers, often lotuses, predominating” [Brown 1988:20-21].

A crackled green glazed granary with a cross-shaped décor resembling a flower with 4 long petals inlaid with brown glaze. The body is divided into 4 panels by an incised brown-glazed vertical line. (See also Brown 1988: pls. I and II). 10-11C. H: 20.5 cm, D: 19 cm. NUS Museum NU30439

A crackled green glazed granary with a cross-shaped décor resembling a flower with 4 long petals inlaid with brown glaze. The body is divided into 4 panels by an incised brown-glazed vertical line. (See also Brown 1988: pls. I and II). 10-11C. H: 20.5 cm, D: 19 cm. NUS Museum NU30439

Monochrome green glaze dish with carved lotus in centre medallion which shows 4 spur marks. (See also Brown 1988: pl. IV.) 9-10C. H

According to Brown [1988: 21-22], brown glazed ware “was relatively rare under the Thanh Hoa fund and was usually monochrome”. They “probably date from the 12th century and include a small number of covered urns, small jars, cups and bowls. The shells often have brown or chocolate-colored bottoms, a common feature of later traded goods. There are only bowls brown on the outside and frost on the inside; these all have an unglazed stacking ring on the inner bottom.” An example is shown on the right below.

Brown monochrome glazed bowl with foliate mouth-rim, 5 spur marks and 8 indistinct stamped motifs in the interior well. 12-14C. H: 7.5 cm; D: 16.5 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-05-0

Brown monochrome glazed bowl with foliate mouth-rim, 5 spur marks and 8 indistinct stamped motifs in the interior well. 12-14C. H: 7.5 cm; D: 16.5 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-05-0

Glazed bowl with foliate mouth-rim, stamped with a décor imitating metal work and 5 spur marks. The pale grey-green glaze is almost white. 14C. H: 9 cm; D: 21 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-019-0

A bulbous celadon bowl in the shape of a crucible, with a wide inverted mouth-rim and carved foot. 12-13C. H: 11 cm; D: 13 cm. NUS Museum S1999-0009-017-0

Finally, Brown [1988:22] tells us: “Among later discoveries in Thanh Hoa, from the 12th to the 13th centuries, there are two types of celadon, both of which are found in earlier trade goods… a This type is usually found on heavy basins, medium sized, relatively simple bowls with rolled rims and carved foot rings. It is thick, opaque, cloudy, dark olive green, and usually rests on white underpants , the underpants can also be thick. Many of these pieces have “chocolate” (underlying brown) bases, and most have spore marks or unglazed stacked rings inside. This species is only occasionally attractive medium green.”

13C. D: 16.3 cm. Saigon National Museum (Photo source: Brown 1988: pl. 7a)

13C. H: 9 cm. Saigon National Museum (Photo source: Brown 1988: pl. 7b)

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

- Brown, Roxanna M., The Ceramics of South-East Asia: Their Dating and Identification, 2nd edn. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Bui Minh Tri and Kerry Nguyen-Long, Góm Hoa Lam, Viet Nam: Vietnamese Blue & White Ceramics, Hanoi, Vietnam: Social Sciences Publishing House, 2001.

- Nguyen Dinh Chien and Pham Quoc Quan, Vietnamese Brown Patterned Ceramics, Hanoi: 2005.

- Frasche, D. Southeast Asian Ceramics: Ninth through Seventeenth Centuries, 1976.

- Gotuaco, Tan and Diem, Chinese and Vietnamese Blue and White Wares found in the Philippines, 1997.

- Lammers, C. and Ridho, A. Annamese Ceramics in the Museum Pusat Jakarta, 1974.

- Miksic, John N. (ed.) Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery, Singapore, Southeast Asian Ceramic Society, 2009.

- Okuda Sei-ichi, Annam Tōji Zenshū, Tokyo: Zauho Press, 1954.

- Rehfuss, D. “Report on the Third Asian Ceramic Conference” in Orientations, Vol. 30, No. 4 (May 1999).

- Richards, Dick, South-East Asian Ceramics: Thai, Vietnamese, and Khmer from the Collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia, Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Rooney, Dawn F. Ceramics of Seduction: Glazed Wares from Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books, 2013.

- Stevenson, John and John Guy, Vietnamese Ceramics: A Separate Tradition, Chicago: Avery Press, 1997.

- White, Margaret. “The Kendi: The Long Journey of a Little Water Vessel”, PASSAGE, May/June 2018, pp. 24-25. Read or download it here.

- Willetts, William. Ceramic Art of Southeast Asia, Singapore: SEACS, 1971, pp. 9-14, quoted extensively by C. Nelson Spinks in his article in the Siam Society Journal article “A Reassessment of the Annamese Wares”, (1976) that can be downloaded here.

- Young, Carol, Marie-France Dupoizat and Elizabeth W. Lane (eds.), Vietnamese Ceramics, Singapore: Southeast Asian Ceramic Society, 1982.

Websites

- www.washingtonocg.org (Washington Oriental Ceramic Group)

- https://asia.si.edu (Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art)

- https://museum.bu.ac.th/en/newsletter/ (Southeast Asian Ceramics Museum newsletters, early ones edited by R. Brown)

Leave a reply