Vietnamese ceramics is a form of art and industry that involves creating ceramic art and pottery, with a history that dates back thousands of years. Archaeological evidence suggests that this art form existed even before the era of Chinese domination in Vietnam.

Although Chinese ceramics had a significant influence on Vietnamese pottery and ceramics during the post-Chinese domination era, it has evolved over time to have a distinct Vietnamese style. Vietnamese potters combined indigenous and Chinese elements, experimented with original and unique styles, and incorporated features from other cultures such as Cambodia, India, and Champa.

During pre-modern times, Vietnamese ceramics played a crucial role in trade between Vietnam and its neighboring countries across all periods.

Narasimha figure, Ly dynasty, 11th century AD

Vietnamese ceramics’ History

Ceramic eaves tile with reversed inscription “vạn tuế” (longevity) found in the site of Nanyue Kingdom Palace (c. 207-111 BCE)

Neolithic

Chinese domination

As China exerted dominance over Vietnam during certain periods, the local Dong Son culture began to wane and Vietnamese ceramics became increasingly influenced by Chinese ceramics.

Classical period

Mộ vò gốm, a ceramic burial jar from Cát Tiên in south Vietnam (4th-9th century CE)

Yue porcelains in North Vietnam, 7th-9th century

Following Vietnam’s reclamation of independence from China in 938, Vietnamese craftsmen began independently designing and manufacturing ceramic productions, distinct from Chinese ceramics, under sovereign royal rules. During the Lý-Trần period, creamy-white celadon and white-brown gốm hoa nâu ceramics were created with local characteristics, and featured dragon “Nāga” decoration and motifs, as well as Bodhi leaf, lotus, water, makara (मकर), and Buddha. Cham script was also inscribed on terracotta bricks used in the construction of religious buildings.

Creamy-white celadon teapot, 11th-12th century

By at least the late 13th to 14th century, Vietnamese ceramics were being exported. Archaeological findings from this time period show that Vietnamese ceramics and coins dating back to 1330 have been discovered in Japan, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

White-brown porcelain, 12th-13th century

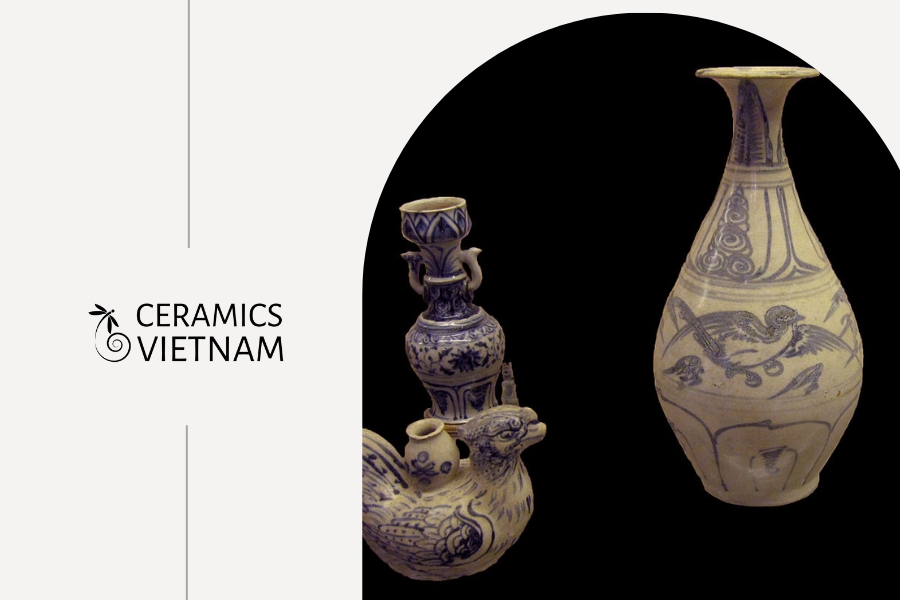

Vietnamese blue and white jar from Chu Đậu kilns, 14th century

During the 15th-century Chinese occupation of Vietnam, Vietnamese potters readily adopted cobalt underglaze, which had already gained popularity in export markets. Vietnamese blue-and-white wares often featured two types of cobalt pigment, with Middle Eastern cobalt producing a vivid blue but being more expensive than the darker cobalt from Yunnan, China.

In the 15th century, around 80% of Southeast Asian ceramic products imported to Trowulan, the capital of the Majapahit Empire, were Vietnamese products, with the remaining 20% being Thai. In the Philippines, Vietnamese ceramics make up 1.5–5% of ceramics found, while Thai ceramics account for 20–40%. Vietnamese ceramics were also a small but present quantity in the 15th-century West Asian market.

Modern

While traditional-style ceramics are still produced and popular, modern ceramics are increasingly being produced for export.Ceramic production areas include Lai Chu in South Vietnam.

One of the most prominent examples of contemporary ceramic art is the Hanoi Ceramic Mosaic Mural installed on the walls of the Hanoi embankment system. The nearly 4 km long Ceramics Road is one of his major projects developed to celebrate Hanoi’s millennium anniversary.

Cát Tiên

The Cát Tiên National Park in southern Vietnam contains the Cát Tiên archaeological site, which was discovered accidentally in 1985. The site stretches from Quảng Ngãi Commune to Đức Phổ Commune, with the most significant archaeological artifacts concentrated in Quảng Ngãi, Cát Tiên District, Lâm Đồng Province, in southern Tây Nguyên. This site was inhabited by an unknown civilization between the 4th and 9th centuries CE, and several ceramic wares were uncovered during excavations.

Bát Tràng

Crackled polychrome glaze pot from Bát Tràng, Nguyễn dynasty period, 19th century

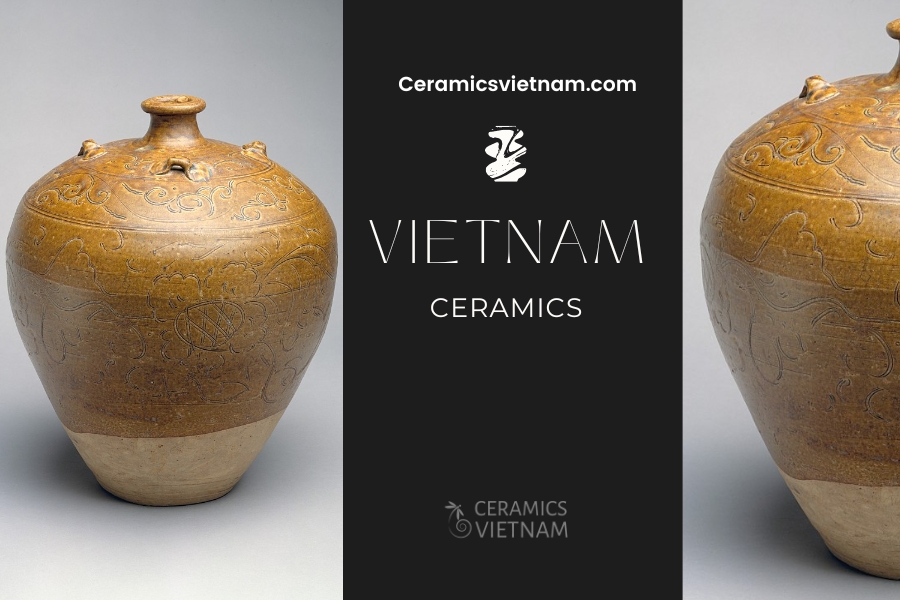

Bát Tràng, a village now located in suburban Hanoi, is renowned for its production of porcelain and pottery ceramics. The village boasts a history of ceramic production dating back to the 14th century CE when the first Bát Tràng kilns were recorded in 1352. The area’s rich clay resources were conducive to the production of fine ceramics, and Bát Tràng ceramics were held in high regard, with products rivaling those of Chu Đậu. Over time, the village’s pottery production was joined by that of Đồng Nai, Phu Lang, and Ninh Thuận. These products were extensively traded by local merchants and European trading ships throughout Southeast Asia and the Far East. Today, Bát Tràng continues to produce bowls, dishes, and vases, not only for the local market but also for export to Japan, a significant market for Vietnamese ceramics. While the gas kiln has become increasingly popular, traditional handmade techniques remain an essential part of the production process. Recently, a new decoration technique using screen printing on rice paper has been applied, mainly for the production of religious items like incense burners. The village also features several old family houses, which preserve the spirit of old Bát Tràng, showcasing large vases and bowls with decorations dating back to the 14th century.

The Bát Tràng Museum, also known as the Museum of Ceramic Art by Vũ Thắng, is the first private museum dedicated to Bát Tràng village.

Chu Đậu

Blue-white dish, from Chu Đậu kiln, Lê Nhân Tông 1450-1460

Chu Đậu ceramics, located in Nam Sách county east of Hanoi, was first discovered in 1983, leading to a series of excavations from 1986 to 1991. The village’s production of ceramics is estimated to have begun in the 13th century, peaking during the 15th and 16th centuries before declining in the 17th century. During the Ming dynasty’s trade hiatus from 1436 to 1465, Vietnamese blue-and-white ceramics filled the void and dominated markets for around 150 years. These Vietnamese wares were found throughout Asia, including Japan, Southeast Asia (Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines), the Middle East (the Arabian port of Julfar, Persia, Syria, Turkey, Egypt), and Eastern Africa (Tanzania).

A Chu Dau dish decorated with pomegranate tree and songbirds, dated 15th century

The famous vase signed by a woman named Bui and dated 1450 in the Topkapi Saray Museum in Istanbul mentions Chu Đậu ceramics. Chu Đậu ceramics exported to Japan were known as (An’nan) Annam wares and made up the majority of the Hội An shipwreck.

An’nan

The trade of Vietnamese ceramics suffered a setback as a result of a decrease in Cham merchants’ trading activities following the 1471 Vietnamese invasion of Champa. Vietnam’s export of ceramics in the 16th century was further hampered by internal civil war, as well as by the Portuguese and Spanish’s entry into the region, and the Portuguese conquest of Malacca, which disrupted the trading system. Portuguese carracks ships in the Malacca to Macao trade docked at Brunei due to good relations between the Portuguese and Brunei after the Chinese allowed Macao to be leased to the Portuguese.

An’nan ware in blue and white

Fragments of Vietnamese ceramics from the 16th-17th century were discovered in a northern part of Kyūshū island as a result of the so-called Nanban trade. Among the fragments was a wooden plate with a character showing the date 1330 on it. It is not entirely clear whether the Japanese went to Vietnam, Vietnamese traders went to Japan, or if it all went through China. According to Vietnamese history records, hundreds of Japanese residents were already present in Hội An port when Lord Nguyễn Hoàng founded it at the beginning of the 17th century.

One well-known example of Vietnamese ceramics is the An’nan wares (安南焼), which were exported to Japan and used in Japanese tea ceremonies, although the high-footed bowls were originally used for food. The bowls have an everted rim, high foot, underglazed cobalt floral decorations, lappets above the base, unglazed stacking rings in the well, and are brown washed on the base. Their diameters range from 9 to 15 centimetres. They were produced in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Hội An wreck

The Hội An shipwreck, located in the South China Sea 22 miles off the coast of central Vietnam, contained a significant cargo of Vietnamese ceramics dating from the mid- to late-15th century. The origins of these pieces were traced back to the kilns of the Red River Delta, such as Chu Đậu, through ongoing excavations since their discovery in 1983. Since all the ceramic wares produced were exported, the only pieces remaining at the kiln sites were the discarded ones. The discovery of the shipwreck was therefore highly anticipated by collectors and archaeologists as it promised the first cargo consisting solely of Vietnamese wares.

Blue-and-white ceramic lampstand, and phoenix-shaped vase ewers dated to the Later Lê dynasty, 15th century. Provenance Chu Đậu kiln, Hải Dương province

In 1996, more than 250,000 intact examples of Vietnamese ceramics were recovered from the shipwreck. The government kept 10% of unique ware for national museums, while the remaining pieces were auctioned off to pay for the recovery costs.

Cham kilns

There were 20 Cham-style kilns situated in Go Sanh, Binh Dinh Province, in central Vietnam, close to the ancient Cham capital of Vijaya. These kilns were used to make brown-glazed stoneware jars, and were known as Cham kilns. They were reconstructed numerous times, which indicates that they were used for an extended period of time. Go Sanh ceramics, which were produced in these kilns, were discovered in various locations, such as Borneo, the Philippines, and shipwrecks such as the Pandanan.

Cham-style stoneware jar, 15-16th century

Leave a reply