Throughout thousands of years of Vietnamese history, the craft that has persisted the longest and undergone continuous evolution is ceramics. In each era, Vietnamese ceramics have emerged with distinct characteristics, personalities, and identities, yet…

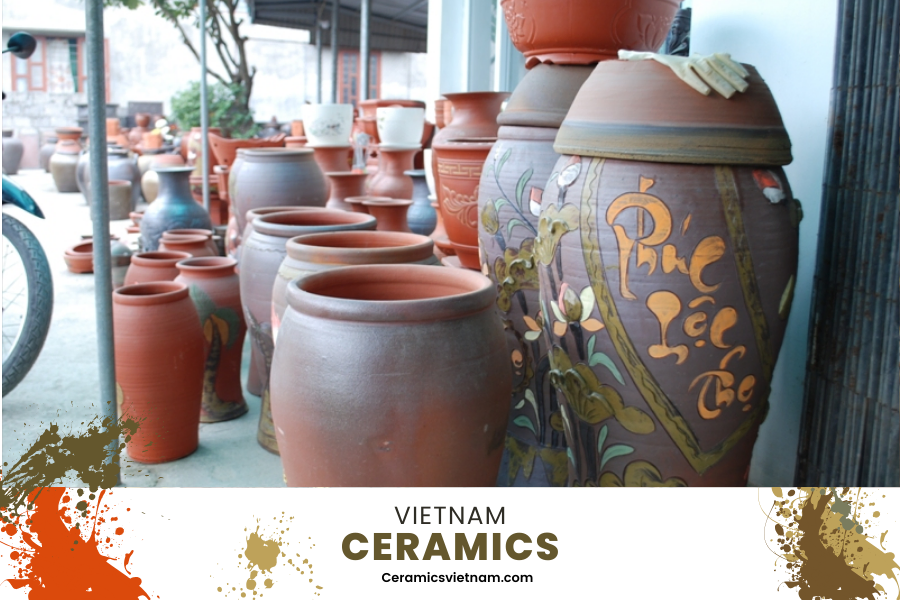

Stretching across the length of the country, from ancient times, every region has had its own pottery craft and kilns. From the exquisite royal ceramics such as Thiên Trường (Nam Định), Thăng Long (Hanoi), to pottery villages like Bát Tràng, Phù Lãng, Hương Canh, Chu Đậu, Thổ Hà… in the north, to Phước Tích (Huế), Châu Ổ (Quảng Ngãi), Gò Sành (Bình Định), Quảng Đức (Phú Yên), Bàu Trúc (Ninh Thuận)… in the central region, and pottery in the southern region with Cây Mai, Sài Gòn, Biên Hòa, Lái Thiêu…; each pottery region represents a typical feature in terms of shaping, glazing techniques, and the diverse forms of Vietnamese ceramics on the map of its development. However, over the centuries, while Vietnamese ceramics once flourished, now they are struggling in the village pond.

Bat Trang pottery village, located on the banks of the Red River, about 10 kilometers southeast of Hanoi’s city center, is one of the most famous pottery villages in Vietnam. With a history dating back hundreds of years, Bat Trang has long been renowned for its traditional ceramics craftsmanship and exquisite products.

Vietnamese ceramic identity

Vietnamese craftsmanship – Vietnamese essence: Vietnamese Ceramics through millennia

Upon breaking free from Chinese domination, the history of Vietnamese pottery has evolved independently, departing from the influences of Chinese, Luc Trieu, and Tang ceramics. The emergence of brown flower pottery during the Ly dynasty (1009 – 1225) marked a distinct shift in form, glaze, and spirit. Throughout subsequent dynasties such as Tran (1225 – 1400), Early Le (1428 – 1527), Mac (1527 – 1592), and Later Le (1533 – 1789), Vietnamese pottery underwent unique transformations.

Renowned collector of ancient Vietnamese ceramics, Truong Viet Anh, notes: “Ly dynasty ceramics, whether brown or ivory, display exquisite forms and intricate decorations. Transitioning to Tran dynasty ceramics, we observe bolder, more rustic lines. The Early Le period witnessed the development of blue-and-white ceramics, which presented an opportunity for Vietnamese ceramics to be exported globally. The artistic techniques flourished during this period, employing painting methods in ceramic decoration. In the Mac and Later Le periods, Vietnamese ceramics distinguished themselves with ancestral worship items. Notably, for the first time in Vietnamese ceramic history, the role of artisans was recognized, with craftsmen such as Bui Thi Do, Bui Hue, Nguyen Phong Lai, Hoang Nguu, and especially Dang Huyen Thong, who created ancestral worship items like lamp bases, incense burners, and ancestral towers.”

From the Nguyen dynasty onwards, the essence of Vietnamese ceramics gradually faded due to the preference for imported foreign porcelain by the ruling elite and merchants. Foreign-style ceramics and commercial ceramics emerged, causing the decline of indigenous pottery. Famous kilns in Bat Trang, Phu Lang, Huong Canh, and Tho Ha only served the common people, failing to expand their presence in the market.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that ceramics from southern Vietnam, such as Cay Mai, Lai Thieu, and Bien Hoa, gained traction in the market, rejuvenating Vietnamese ceramics. According to Nguyen Huu Phuc, head of the antique club in Thuan An, Binh Duong: “Cay Mai ceramics from the Saigon-Cholon region were primarily used for ancestral worship in Chinese temples. When the Cay Mai kiln closed, artisans moved to Lai Thieu, adopting Quang, Trieu Chau, and Phuc Kien ceramic styles. In 1902, the Bien Hoa School of Arts was established, offering ceramic training, and by 1922, Bien Hoa ceramics had appeared in exhibitions at the Marseille Fair, as well as the Paris International Exposition in 1925 and 1932.”

Bien Hoa ceramics conquered the European market, while Cay Mai ceramics met the demand within the Chinese community. Lai Thieu ceramics captured a large market in the southern region and neighboring countries such as Laos, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Many Lai Thieu ceramics from the 1960s can still be found in major antique markets around Manila, Jakarta, and Pasig City. These distinctive characteristics, identities, and market influences have partially restored the glory of Vietnamese ceramics.

During this period, besides craftsmanship, pottery making began to associate with the names of renowned artisans, such as Ngo Khon, Lam Dao Xuong (Lai Thieu ceramics), Thai Van Ngoc, Duy Liem (Thanh Le ceramics), Bay Van, Ut No (Bien Hoa ceramics).

Thanh Le pottery lesson

Vietnamese craftsmanship – Vietnamese essence Vietnamese Ceramics through millennia

Through many ups and downs, as time progressed, the essence of Vietnamese ceramics gradually faded in the global ceramic flow. Especially after the 1970s, Vietnamese ceramics nearly stagnated.

Subsequently, traditional pottery villages gradually revived but chased after trends. Copycat designs proliferated, with villages focusing more on quantity and orders rather than preserving their identity. Ceramic artisans lacked independence and creativity. The collaboration between ceramic artists and traditional pottery villages was not strong, and the lack of practical experience hindered the development of Vietnamese ceramics.

The success of Thanh Le ceramics in the 1960s – 1970s serves as a lesson in inheriting and enhancing the strengths of Vietnamese ceramics.

Originating from a lacquer workshop in Binh Duong in 1943, Thanh Le ventured into ceramics in the 1960s. In Lai Thieu, Binh Duong at that time, ceramics were dominated by the Chinese, with numerous prestigious kilns such as Quang Hoa Xuong, Thai Xuong Hoa, Duyet An, Hung Loi, Dao Xuong, Vinh Phat, Huong Thanh, Quang Hiep Hung, Van Hoa, Nhu Hop… Establishing a Vietnamese ceramics kiln to compete, without prior experience in pottery-making, was a significant risk.

To dominate the market in the South and Southeast Asian countries, Thanh Le gathered skilled ceramic artisans from Lai Thieu, Binh Duong, Bien Hoa, to create large-sized clay molds, ranging from 0.8 to 1.1 meters in height. From the beginning, Thanh Le ceramics exhibited a difference, as most Lai Thieu ceramics were household items with small sizes.

Thanh Le’s ceramic-making process differed from others due to its selection of master artisans. Ceramic throwing was performed by Bay Van – the king of Bien Hoa ceramics, while sculpting bas-reliefs on ceramics was done by Ut No, with designs by renowned artists such as Duy Liem, Thai Van Ngoc, and Nguyen Cao Nguyen. Each product underwent rigorous processes, and any flaws upon kiln opening resulted in rejection, with only truly perfect pieces retained.

Tu Phep, the workshop manager of Thanh Le ceramics in the 1960s, recounted: “Mr. Le was very demanding. After making 100 ceramic vases, upon firing, if any faults were found, he smashed 80 of them. The first batch of blue-and-white ceramics, with over 100 large vases, had issues like living core, glaze burning due to lack of experience, all of which were ordered to be destroyed. The finished ceramic products, when brought to Saigon, at a time when my daily wage was 10 dong, were sold for a minimum of 300 dong.”

While Lai Thieu ceramics featured imported themes such as Eight Immortals crossing the sea, Bamboo grove and chrysanthemum, Su Vu herding goats, Thanh Le replaced them with Vietnamese historical events like the Bach Dang River battle, the Trung Sisters’ uprising against the Han, the Ngoc Hoi-Dong Da battle, replacing mythical creatures with native Vietnamese imagery like plum blossoms and cranes. The process of Vietnamese adaptation became simplified, and upon viewing the products, their origin from Vietnam was immediately identifiable.

The emphasis on identity and craftsmanship by Thanh Le was highly appreciated by consumers, even at higher prices, due to the value of the stories behind each ceramic piece. Thanh Le ceramics continued the success of the lacquer workshop, exported to countries worldwide. To this day, Thanh Le ceramics, although classified as antiques, hold high value compared to other ceramics of the same period.

Leave a reply